Introduction

Achieving ‘loud’ masters as an end product for distribution is a prevailing expectation within the creative system of music production, presumed to be as a result of the ‘louder is better’ paradigm; “the established assumption that a ‘louder’ recording will invariably, by comparison, be preferable to most listeners” (Taylor & Martens: 2014, p. 1). For more than half a century, since the birth of modern mid 20th Century popular music, processes that ensure ‘loudness’ in masters have thrived alongside technological advancement in recording and reproduction. The history of recorded music has shown us that with every new reproduction format introduced (for example vinyl records and compact disc), the quest for loudness has pushed the boundaries of its operation. Once one artist, seen here as a creative agent, had reached a new level of loudness all other creative agents had to follow so when comparisons were made between recordings, one was not seen as softer and in a sense, inferior. Therefore, in this manner, loudness can be viewed as a sound quality judgement (Weymouth: 2012, p.1).

Although we can observe moments in recorded music history whereby technological advancements heralded new capacity for level increases, the introduction of digital audio technology by far provided the most potent form of ‘loudness’ in the form of hyper-compression [1]. Digital ‘look-ahead’ limiters and multi-band compressors provided surgical like precision to significantly reduce musical dynamics to create ‘loudness’ on an unprecedented scale; synonymous with popular music of the late 20th and early 21st Centuries. Surprisingly, with its widespread use, the existence and persistence of the myth surrounding the ‘loudness’ of recordings, despite the accumulated scientific evidence regarding the deleterious effects of hyper-compression, has been largely overlooked within an examination of the creative system of audio production. There is a distinct tension between the empirical evidence of applied science and the subjective interpretation of creative agents in that the practical use of hyper-compression continues unabated.

As part of a larger research study, this paper proposes a framework for an examination of these tensions from a systemic perspective where agency and the symbolic and social structures they engage with, operate within what Williamson and Cloonan define as the music ‘industries’ (2007, p.1). These industry sectors, or industries, perform as discrete systems individually but also act, at the same time, as part of a larger scalable system centred around the production and distribution of music recordings (artefacts). A synthesis of both objective and subjective viewpoints is then suggested to examine these creative systems (Csikszentmihalyi: 1998, 1999), coupled with Bourdieu’s theories of habitus and capital (1993, 1996), to expose the relationship between agency and structure in the use of hyper-compression as a creative tool.

Background

‘Perceived loudness’ [2] has been a fundamental issue in audio production since the commercialisation and subsequent broadcast of modern popular music (e.g. rock ‘n’ roll) in the mid 20th Century. Thiele described 1957 as the year that Western popular music “changed forever” with the introduction of jukeboxes, “installed in large quantities in public places” (2005, p. 1). These “brightly lit monsters” were a catalyst for the pursuit of loudness on vinyl recordings (ibid). Since the playback level was fixed and the customer had no control over volume, record companies were presented with the problem of getting their track to stand out from the others, loudness became the preferred method (Weymouth: 2012, p. 1). Thiele goes on to conclude that competing for program loudness “survived the age of the jukeboxes and permanently changed the culture of much popular music” (2005, p. 1). George Martin, the Beatles’ producer spoke of how baffled he was at how hot [3] American records were and wanted to get the Beatles that sound (Martin et al.: 1995, p. 143). The Beatles in fact lobbied their record label Parlophone to “get their records pressed on thicker vinyl so they could achieve a bigger bass sound” (Southall: 2006, online). In the documentary, Queen: Days of Our Lives (O’Casey: 2011), Freddie Mercury and Brian May are seen in the early 70s discussing a desire to get their records as loud as physically possible, hence sending their masters to the US for an American style loud cut. Motown were “particularly adept at this” (Thiele: 2005, p. 2) and adopted a standard called ‘loud and clear’ (Vickers: 2010, p. 3) using a multitude of methods to achieve maximum level while retaining clarity [4].

Fast-forward to the 1990s and this ethos that ‘louder is better’ is even more pervasive. The introduction of digital audio technology (the compact disc or CD) armed audio practitioners with unparalleled ability to increase the level of audio masters and negated all complications associated with the previous analogue media [5]. Mastering engineers were now “not constrained by the limitation of the sound storage medium anymore” as there were “hardly any technical limitations for the CD” (von Ruschkowski: 2009, p. 222). Coupled with new digital forms of dynamic range compression (DRC) this technology created what has been described as a competition to be the ‘loudest’. The use of hyper-compression in the mastering process has been dubbed by both media and industry as the so-called ‘Loudness Wars’. Vickers is blunt in his description of this standoff as “a zero sum mindset of ‘beating the other guy’” via the use of loudness (2010, p. 17). This vivid description by Vickers is certainly correctly attributable to a war that was waged on a different front more than a decade earlier; New York in the early 1980s with FM radio stations WHTZ (OR Z-100) and WPLJ. The two featured combatants, were radio broadcast engineer Frank Foti (WHTZ) and station director Larry Berger (WPLJ), whose exploits into loudness were reported by Greg Milne in Perfecting Sound Forever: An Aural History of Recorded Music (2010). Milne’s often humorous account of the two stations ‘slugging it out in a louder takes all’ approach, indeed makes entertaining reading. However, it is reported that Robert Orban, the inventor of the ‘Opimod’ radio processing unit that incorporated a range of loudness inducing technology was the first to coin the term ‘Loudness War’ in response to the battle for loudness between rival FM radio stations in general. This term was then reappropriated to describe the ensuing battle for loudness between music recordings.

If we move forward once again to the 1990s, we see a similar rationale for the second loudness revolution but the motivation becomes vastly more complex. To this day, a definitive explanation of why hyper-compression is so pervasive in music production is evasive. One of course should take into account the complex creative and cultural context of music production and musical genre, and also the effect the diffusion of digital technological innovation has had on the way music is produced and subsequently reproduced. There is, however, still the underlying argument that artists have to maintain a certain degree of loudness to maintain competitiveness in the industry and this is prevalent in the literature on the subject. Once one artist had reached a new level of loudness, all others had to follow so when comparisons were made between recordings, one was not seen as being disadvantaged by being perceived as softer. Despite the overwhelming volume of scientific evidence in existence that discusses the deleterious effects hyper-compression has upon audio quality (for example see: Nielson et al.: 1999, 2000, 2003; Lund: 2004, 2006, 2007; Thiele: 2005; von Ruschkowski: 2009; Vickers: 2010, 2011; Deruty: 2011), the practice continues virtually unabated.

At the core of cognitive responses that are claimed to be attributable to the use of hyper-compression in music production is the premise of a predilection for louder over softer sounds. As Taylor and Martens explain:

Since the 1950s, the commercial music industry has witnessed large increases in the relative level of sound recordings. This shift was arguably predicated upon the established assumption that a ‘louder’ recording will invariably, by comparison, be preferable to most listeners. This constellation of beliefs and practices is termed here as the ‘louder is better’ paradigm. This deeply entrenched paradigm draws upon two distinct considerations. Firstly, preferences may be due to the innate workings of human hearing, which displays a more linear frequency response at a higher sound pressure levels (Fletcher & Munson, 1933). Secondly, louder music may engender a heightened psychophysical response (Levitin, 2006; Viney, 2008). These considerations have led artists and music companies to actively seek increases in recording levels, such that their product was relatively ‘louder’ than its competitors (2014, p. 1).

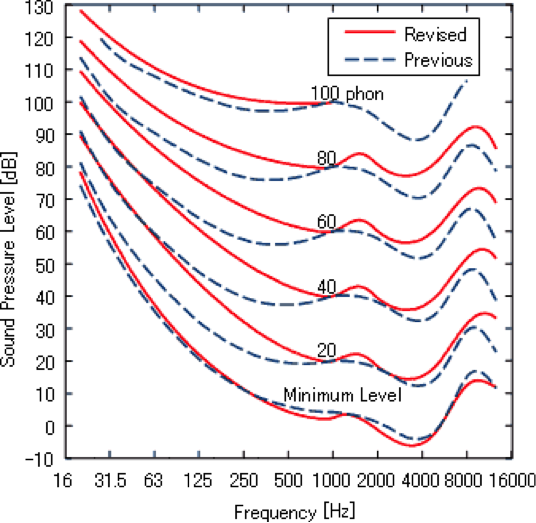

The rationale behind this claim stems from the non-linear frequency response of the human auditory system, which illustrates “one of the fundamental characteristics of auditory sense” (ibid). Put simply, low and high frequencies are more audible as the sound intensity increases and visa versa. The equal loudness contours presented in ISO 226:2003 represent what is commonly known in the literature as the ‘Fletcher Munson curves’ or the ‘equal loudness contours’, illustrated in figure 1 (ISO, 2003).

Figure 1: The ‘Fletcher Munson curves’. This illustration depicts a comparison between the current (ISO 226:2013) and the original characteristics published by Fletcher and Munson of the equal-loudness-level contours in 1933. The curves lines represent the perception of equal loudness at varying frequencies, with the greatest sensitivity at approximately 3kHz. (Image sourced from the National Institute of Advanced Science and Technology, Japan)

As a result of this non-linear frequency response, recordings that are perceived at a higher playback level will provide greater perception of detail in the low and high frequencies and alternatively, loss of detail at lower playback levels (Vickers: 2010, p. 4). Therefore, if a comparison between recordings is conducted as Milner explains “of music at two different volumes and [you] ask people which sounds better, they will almost always choose the louder, partly because more of the frequencies are audible” (Milner in Vickers: 2010, p. 4), hence “this quirk of hearing…has played an important role in enabling the loudness war” (Vickers: 2010, p. 4). Although it is unlikely that this predilection for louder recordings can be solely attributable to this one psychophysical phenomena and there may be other factors that requires further investigation, this assumption remains a core determinant within the literature.

Agency, Structure and the Creative System

Hyper-compression has now spent more than two decades entrenched in the digital paradigm of popular music production and, in particular, mastering. It is clear that a new interpretive model is well overdue that adequately explains not only the objective audio qualities of mastered audio (which is arguably over-represented in the literature) but how this is subjectively engaged by those responsible for the production of music, the critique of music and those that listen to music. To begin such an investigation, one may wish to first examine those that produce musical artefacts (the agent) and the environment in which the agent operates (structures) to get a better understanding of why hyper-compression is such an ingrained part of popular music production. Hence an examination from the point of view of: the agency of the music artist/practitioner, the agent’s ability to make choices; and the structures that are available to that agency by the networks present, that is, the opportunities and limitations for choice of action.

The agent has been defined, depending on which theorist you prefer, as a “person” (Sawyer: 2006, p. 123), an “individual person” (Csikszentmihalyi: 1997, p. 28), an “actor” (Giddens: 1984, p. 5), “a group, a work team or an ensemble” (Abra: 1994; John-Steiner: 2000; Paulus & Nijstad: 2003; Sawyer: 2003 – Quoted in Sawyer: 2006, p. 123), or a “producer” (Bourdieu in Johnson: 1993, p. 6). Csikszentmihalyi claims that “creativity occurs when a person [agent], using the symbols of a given domain…. has a new idea or sees a new pattern” (1997, p. 28). Therefore the agent’s ability to make choices in the creative process that Csikszentmihalyi describes, is their agency, which Giddens alternatively defines as making decisions and acting upon them (1984, p. 5). Structures exist in any domain and field whether it is music production or quantum mechanics. They present both opportunities and limitations for choice of action, since “structure is not to be equated with constraint but is always both constraining and enabling” (ibid p. 25). McIntyre describes structures as “those things or objects thought to determine actions and behaviours” (2012, p. 4) and that actions and structures are axiomatically interrelated:

Human agents, all seven billion of them, are inescapably implicated in a set of structures that both limit and enable their agency; agency, in this case, being the ability of a subject to make choice and act on that choice (ibid).

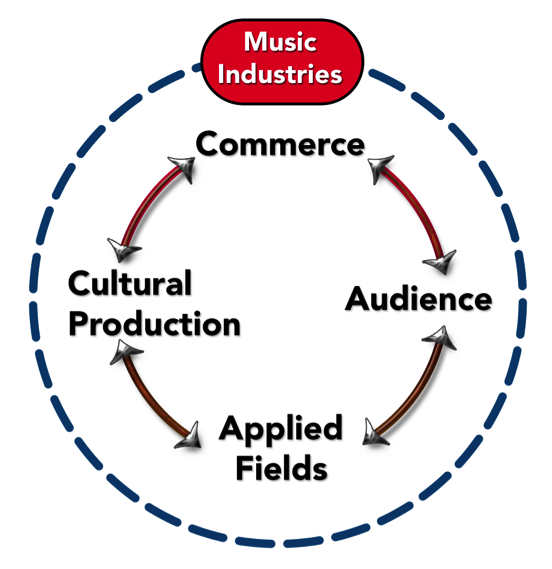

When considering the production of music, the agent, whether they are a composer, producer, mastering engineer, A&R manager or music director etc., clearly operate within a network of scalable systems which is commonly referred to at one scale as the music industry. We can start by defining what exactly that is, and is it a singular entity as the title suggests? Williamson and Cloonan assert that the use of the singular term ‘industry’ implies “that the industry is a homogenous unit with shared objectives and interests” (2007, p.1) and is an abuse of the term. It is at best, an “out-dated and an inaccurate portrayal of the organisational structure of the global music economy” (ibid). They quote Wilson et al. (2001, p. 94) that “there is a lack of consensus as to precisely what types of businesses are representative of ‘the music industry’”, suggesting the use of the term ‘music industries’ (plural) to encompass the many organisational entities (or systems); record production, audio and electrical engineering, research and development, music publishing, artist management, concert promotion, graphic design, manufacturing, video production, online music services and of course the audience. Hence, we can identify within this list four separate interrelated and recursive broader sectors related to the music industries, as illustrated in figure 2: those that develop processes (applied fields); those that produce artefacts (cultural production); those that promote and sell the artefacts (commerce); and of course those that consume the artefacts (audience). Each of these sectors has a range of inherent structures that again present both opportunities and limitations for choice of action.

Figure 2: The ‘music industries’ identified as four separate, interrelated and recursive broader sectors: cultural production, commerce, audience and applied fields.

With these definitions in hand, we return to the fundamental question; why is hyper-compression so deeply rooted in music production? What structures are in place within the music industries that strongly influence agents to adhere to its use? Rogers & Kincaid, quoting Watzlawick et al (1967), assert that “human systems are connected and coordinated, not by mechanical means or by the force of matter and energy, but rather by the exchange of information” (1981, p. 61). This proposition highlights two fundamental ways of viewing communication. One is to place emphasis on the “transmission of information from one point to the next” (McIntyre: 2012, p. 1), and we need look no further within the topic of hyper-compression than to the scientific analysis of the signal path in the definitive work of Nielson et al. (1999, 2000, 2003) and Lund (2004, 2006, 2007) as an example of this approach. These scientific findings have contributed to a wide spread consensus within the realm of audio research that hyper-compression is damaging to audio signal quality. It not only introduces unwanted artefacts such as non-linear distortion, but also distortions in musicality via the removal of dynamics claimed to “[rob] music of its excitement and emotional power” (Vickers: 2010, p. 5). Despite this knowledge, practitioners continue to rely on the hyper-compression process to gain loudness in recordings and its rampant use prevails. The second position argues that “the generation of meaning is not to be found in a linear act of communication, but is instead processed within particular cultural contexts” (McIntyre: 2012, quoting Schirato & Yell: 2000: p. 8). With these broad ideas in mind we can pose a specific question about the role hyper-compression actually plays in the exchange of information that is popular music. Considering its use is endemic, does the importance lie not only in what is the signal but also in what it communicates to its audience? Instead of examining principally from only one of these viewpoints (which seems to have proven inadequate), it is suggested that a systems approach be taken that can support a confluence of the two.

To support this argument we can first look to McIntyre who states that rather than excluding a signals approach or a meaning making approach, a “synthesis may be found in seeing acts of communication in a similar manner to the way creativity and cultural production has been theorised in recent research, that is, acts of communication come into being as emergent properties of what may be best described as a system of communication at work” (2012, p. 1). We can relate this statement directly to the composition, performance, production and distribution of popular music under the broader term of cultural production, and posit this as the core of the music industries; the production and consumption of musical artefacts.

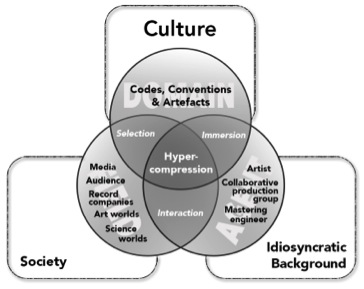

Furthermore, the stratification of sectors within the music industries, the various interrelated roles each sector plays and the domain structures evidently used by agents could be viewed overall as a ‘creative system’ (figure 3); arguably best understood in terms of Csikszentmihalyi’s systems model of creativity:

Creativity results from the interaction of a system composed of three elements: a culture that contains symbolic rules, a person who brings novelty into the symbolic domain, and a field of experts who recognise and validate the innovation. All three are necessary for a creative idea, product, or discovery to take place. (1997, p. 6)

This three pronged framework can be described alternatively as the:

- Domain: the sum of all knowledge, symbolic structures and artefacts.

- Field: the users who work within and understand the domain and provide the social structures of the music industries, who act as ‘gatekeepers’ to new inclusions to the domain.

- Agent: an individual or collective that actively works with and within the symbolic and social structures of the music industries to create new ideas to be selected by the field for inclusion into its domain. (ibid)

Figure 3: The ‘music industries’ interpreted using Csikszentmihalyi’s systems model of creativity, where a framework of domain, field and agent is utilised.

The role of the field as one of the “three ‘moments’ of the same creative process” (Csikszentmihalyi: 1988, p. 329), is to “decide whether a new idea or product should be included in the domain” and members of the field are described as the ‘gatekeepers’ of this new knowledge (Csikszentmihalyi: 1997, p. 27). The ability of any field to perform in relation to a domain of knowledge is also paramount to the success in which a field cultivates its knowledge base (Csikszentmihalyi: 1999, p. 327). If the primary role of the music industries is the production and consumption of artefacts (music) as mentioned, it would suggest that the capacity of the field to provide essential structures for this undertaking is vital in creating the opportunity for creativity to actually occur as “agents do not act in a vacuum, but rather in concrete social situations governed by a set of objective social relations” (Johnson in Bourdieu: 1993, p. 6).

Agents working within a field require access to, and an intimate knowledge of these structures “to make a creative contribution” (Csikszentmihalyi: 1988, p. 330) as “a person cannot be creative in a domain to which he or she is not exposed” (Csikszentmihalyi: 1997, p. 29). Bourdieu describes this acquired knowledge as habitus or a “feel for the game”, which encompasses “a set of dispositions which generates practices and perceptions” that are necessary to participate in the field and be a “player within the game” (Johnson in Bourdieu: 1993, p. 5). He posits this knowledge as various forms of capital that exist as currency for trade in power relationships within the field. These can be summarised as; “economic capital” (monetary), “social capital” (social connections), “cultural capital” (competence) (Bourdieu: 1986, p. 243) and “symbolic capital” (prestige, celebrity), of which the latter two are “particularly important in the field of cultural production” (Johnson in Bourdieu: 1993, p. 7). From Bourdieu’s perspective, all practices are “oriented toward the maximising of material or symbolic profit” (Bourdieu: 1990, p. 209), in what McIntyre labels an “arena of social contestation” (2008, p. 1). These theories can be readily associated to the main objectives of the music industries represented as acquiring popularity (symbolic capital), resulting in economic profit (economic capital). Although Csikszentmihalyi’s theory “tends to emphasise its Darwinian functionality” (McIntyre: 2008, p. 1), seen in its “right place at the right time” mindset (Csikszentmihalyi: 1997, p. 28-29), Bourdieu’s Marxist mentality of struggle and conflict is not far removed from this conception as they both indicate a necessity to gain access to the field with the aspiration of the aforementioned objectives.

The music industries as a field representing the various interrelated domain sectors mentioned, constitute a system of sub-fields that Bourdieu denotes as a “social formation” that is “structured by way of a hierarchically organised series of fields”, whose “structure, at any given moment, is determined by the relations between the positions agents occupy in the field” (Johnson in Bourdieu: 1993, p. 6). Bourdieu believes that fields are dynamic and modified by changes of an agent’s position, which is most likely the case with many fields, however it could be argued that the greatest catalyst for changes to the structures used within the music industries were those exemplified by access to digital technology. This access has radically altered pre-existing power structures in the field. The introduction of this technology has given rise to what could be considered a new form of ‘techno capital’ that has empowered the audience as prosumers to challenge established traditional networks. Bourdieu’s view that fields can have specific forms of capital that fit the particular dynamic of a field supports this idea. For example, the access to low cost computer based recording equipment has significantly diminished the role played by large format studios and professional recording personnel, and likewise on-line music services have had a dramatic effect on the pre-existing model of physical distribution of music (Viney: 2008, p. 56). It could be argued that access to this technology has redistributed the power from the traditional towers of influence to a broader assembly.

Hyper-compression can also be seen to function as a form of cultural capital primarily linked to the skills, techniques and knowledge associated with digital technology. Without the diffusion of this new digital technology into the field providing processing accuracy never before experienced, hyper-compression would simply not be achievable. von Ruschkowski asserts that “digital dynamics processors are broadly seen as the main premise for the ‘Loudness War’” (2009, p. 222). In defence of his claim, he quotes US mastering engineer Bob Ludwig who declares, “thank God they weren’t invented when the Beatles made their music!” (ibid). It is clear that Ludwig is implying that hyper-compression, as a structural determinant in music production, could have happened much earlier if this technology were available in those times.

At the onset of this technology and before being widely available, only those via their positioning within the field due either to their substantial symbolic, cultural, social or economic capital within the industry, had access. Like all new technology, digital processing was initially hard to come by and prohibitively expensive. This gave some artists an early advantage over their competitors with an ability to make masters louder than everyone else. This dynamic quickly changed when the technology became commonplace (as with most technological advancements) and introduced another scenario that Weymouth describes as an “archetypal example of the famous Prisoner’s dilemma – a theoretical two-player game in which the two players may not co-operate, even if it seems to be in their best interest” (2012, p. 3). With both parties armed with the same technology and ability to make loud masters, a situation developed not unlike a ‘cold war’ with either party unwilling to back down for fear of being uncompetitive and something that Katz explains as a “vicious circle of loudness envy” (2010, online). Vickers takes the concept one step further by stating that:

The two-player Prisoner’s Dilemma does not effectively model a situation like the loudness war, in which there may be dozens, hundreds or thousands of players, each of whom have limited interaction with (and limited leverage over) the others. This type of situation is a “social dilemma,” in which individually reasonable behavior leads to a result in which everyone is worse off. As Kollock writes, “a group of people facing a social dilemma may completely understand the situation, may appreciate how each of their actions contribute to a disastrous outcome, and still be unable to do anything about it” (2010, p. 15).

As a result, hyper-compression can then be seen as a pre-requisite for recordings before they are presented to other sectors-members of the field for scrutiny as illustrated by producer Tony Visconti (quoted in Anderson: 2008, online); “One (artist) once turned to me after I made a request for more dynamics and said, ‘I have a reputation to uphold, I can’t make it that quiet’.” Once considered a ‘competition’ to be the loudest to capture the most attention, when the maximum possible level had been achieved and no further advantage could be attained by any one artist, it could be argued that at this point hyper-compression had transformed into a structure that agents were bound by. Mastering engineer, Chris Athens confirms this assumption by stressing “nobody really wants to have a record that’s not as loud as everybody else’s in an iTunes playlist” (quoted in Smith: 2008, online). It could also be argued that when the adoption rate of hyper-compression had reached a point of saturation and was accepted by the field as a standard operation, the process became a pre-requisite for artists to be able to enter and maintain relevance in the field.

Deruty and Tardieu’s research found that 2004 heralded a peak and subsequent plateau in the magnitude of the use of hyper-compression and could be seen to indicate that the field had finally signalled a systematic inclusion of the process into the domain (2014). It could also be argued that hyper-compression had moved away from being an agent’s choice to that of a structural determinant in the production of popular music, causing some controversy. The topic by this time had become the subject of intense debate amongst various sub-fields of the music industries. The scientific fraternity were the first and largely the most vocal to negatively weigh into the debate along with a collection of sympathetic audio practitioners and so-called audiophiles. The media eagerly reported the issue due to the attention garnered with varying degrees of accuracy, viewpoint and understanding of the issue (for example see: Jones: 2005; Emery: 2007; Sreedhar: 2007; Masterson: 2008; Anderson: 2008; Smith: 2008; Clarke: 2009; Donahue: 2010; Mauch: 2011; Inglis: 2011; Paul: 2011; Reierson: 2011; and Michaels: 2012). Specific cases of excessive hyper-compression were then highlighted, in particular that of Metallica whose 2008 album release Death Magnetic becoming what many described in the media as the ‘poster boys’ of hyper-compression, and indeed one of the most hyper-compressed albums in recorded music history (Metallica: 2008). It was at this point that the audience entered the conversation with an alleged 22,000 fans making complaint of the album’s excessive loudness (Smith: 2008, online). Hyper-compression’s dominance within mastering practices has steadfastly remained an intrinsic part of music production since with little signs of abating. As producer/musician Butch Vig explains, “compression is a necessary evil. The artists I know want to sound competitive. You don’t want your track to sound quieter or wimpier by comparison. We’ve raised the bar and you can’t really step back.” (quoted in Lamere: 2009, online). Mastering engineer Stephen Marcusson takes a positive but measured approach:

I don’t want to be averse or buck my peers, but I don’t see it as a problem. I see the abuses of loudness as a problem, when the artefacts of loudness are unpleasant distortions that take away from the listening experience. But a really rocking, loud, well-mastered CD is great. It’s fun, it’s competitive, the music translates (quoted in Jones 2005, online).

Southall (2006) and Weymouth (2012) position the 1996 album What’s the Story Morning Glory? by UK group Oasis as one of the catalysts of what can now be called the hyper-compression age, in which a BBC report [6] described it as “the loudest album in the world” and “breaking new ground at the time” (Oasis: 1996). Southall attests that the album was a ‘jump-the-shark’ moment as far as CD mastering goes” and adds that it arguably “became so successful in the UK precisely because it was so loud; it’s excessive volume and lack of dynamics meant it worked incredibly well in noisy environments like cars and crowded pubs, meaning it very easily became a ubiquitous and noticeable record in cultural terms” (2006: online). The general public the world over had never heard of an album mastered so loud and it was certainly aesthetically significant in that respect alone. Barry Grint, who by his own report had mastered the album at Abbey Road Studios (although who actually mastered the album is of some conjecture) claims that the album was almost rejected when it was sent to the United States for released; “They said, ‘It looks like a square wave. Does this guy not know what he’s doing?’ Two weeks later, they were all doing it” (SOS: 2010, online).

In terms of creativity this would suggest the band was single-handedly responsible for the loudness paradigm, however this is far from the case. We can ignore this ‘romantic’ view of creativity that Kant embraced as “a unique and spontaneous act that introduces a leap in ordinary natural processes” (Rothenberg & Hausmann: 1976, p. 29) and look to Csikszentmihalyi’s proposition that “creativity does not happen inside people’s heads, but in the interaction between a person’s thought and a sociocultural context. It is a systematic rather than an individual phenomenon” (1997, p. 23). Considering that the loudness paradigm had been deeply rooted in radio, advertising and music for decades previous, as suggested by Thiele (2005), it could be argued that Oasis, enabled by new digital technology, simply reinvented an old idea in a new way to gain a competitive edge. Similarly, we can dismiss the myth of genius “which also pervades our society” and “assumes that truly creative acts involve extraordinary individuals carrying out extraordinary thought processes” (Weisberg in Sternberg: 1999, p. 148). Oasis may have just been the first successful band brimming with symbolic capital to employ hyper-compression, heralding the process to the world’s attention, but were utilising something that had been developing for decades. They were most likely responsible for instigating its widespread use, but cannot take full responsibility for its uniqueness.

If we look to the systems model for an explanation, it would suggest that Oasis introduced a novel idea that the ‘field of experts’ (those involved in the music industries) recognised as valid, bringing forth a change in the symbolic domain. Oasis, or at least the producer and mastering engineer they employed, had intimate knowledge of the domain as “you cannot transform a domain unless you first thoroughly understand how it works” (Csikszentmihalyi: 1997 p. 90). According to Oasis’ producer Owen Morris (who also claims he mastered the album), his rationale was that “given that I had no confidence in the sonic integrity of my mixes I had decided that I would attempt to use VOLUME (i.e. quantity rather than quality!)[sic]” [7]. This suggests that hyper-compression already existed within the knowledge base of the domain and this was not an ‘inspirationalist’ act of a genius, but an action occurring within a system; “as the research literature into creativity also tells us, each new idea is firmly built on a set of antecedent ones” (McIntyre: 2012, p. 7).

Csikszentmihalyi asserts that there is no such thing as a singular agent, acting solely on their own as this is akin to the romantic notion that creativity comes from a divine source that is separate from earthly influence (1997, p. 23). With agency comes all the influence of history and domain knowledge, therefore you can’t say that the one singular entity is acting purely from their ‘own ideas’; “they are bound to structures that pre-exist them” (Csikszentmihalyi: 1997, p. 23). Giddens and Bourdieu although coming from different perspectives both allude to agency and structure as having a recursive relationship. Giddens suggests a “duality of structure” in that “structures make social action possible, and at the same time that social action creates those very structures” (Haralambos & Holbern: 1995, p. 904). Bourdieu on the other hand “uses the mechanisms and concepts of habitus, field, cultural and social capital and field of works to do this” (McIntyre: 2012 p. 5). This talk of structures of course then motivates the question of what exactly is ‘free will’ if agency is so determined by structure? Schinato & Yell suggest that “theories of practice have always found difficulty coping with the problem of the extent to which practices are the result of free choice or intentionality, on the one hand, or structured, predetermined and unconscious, on the other.” (2000, p. 143). Agents and their agency have to function within the structural limitations of the field but that does not mean they are not exercising free will, they are just making choices from what is available to them.

The discussion of choice is particularly felicitous when considering the use of hyper-compression. The limitations placed on all and sundry to compete in the music world, the motivation to succeed, the “‘investing’ one’s (academic, cultural, symbolic) capital in such a way as to derive maximum benefit or ‘profit’ from participation” (Johnson in Bourdieu: 1993, p. 8) drives the ‘reproduction’ of hyper-compression in the social system of music production as Giddens theory of ‘structuration’ suggests (van Krieken et al.: 2005, p. 904). We can locate agents from this social system within the sub-fields of production, promotion and consumption.

The process of hyper-compression is conducted during the production stage known as ‘mastering’ which Rumsey describes as a:

…process of ‘finishing’ in audio production that aims to unify and improve the final quality of a project. In the age of analog audio it tended to involve optimizing the sound so as to overcome or accommodate the limitations of the delivery medium. With the advent of the digital age an apparently transparent delivery channel was offered, requiring mastering engineers to rethink some of their reasons for existence. Now, we live in a time of multiservice digital delivery methods that have a wide range of quality effects and limitations, giving rise once again to a challenge for mastering, albeit of a slightly different nature (2010, p.1).

The mastering engineer, who conducts the mastering process, is at the frontline of the hyper-compression debate primarily because they are the agent who is seen as largely responsible for the act of making a recording ‘loud’. However, the literature indicates there is a greater hierarchy of agents involved in the decision making process such as the artists, producers, and record company personnel (Vickers: 2010; 2011). It could therefore be implied that mastering engineers merely provide a service but this also is over simplifying the relationship that the mastering engineers have with their clients. Mastering engineers are considered valuable as Rumsey asserts, as the final link in the production chain that seek a “form of audio truth”, and a “mediation” between client expectations and reality (2010, p. 4). Like any other personnel chosen for a given project, mastering engineers are sought for their creative ability and stature in the domain; their cultural and symbolic capital. As Jeff Murphy asserts, “mastering is the final creative stage in the production of your recording” (2002, online). This is also reinforced by mastering engineer Bob Katz who explains that ‘mastering is the last creative step in the audio production process’ (Katz, 2002, p. 11).

In the literature, mastering engineers are of course representative of many personal opinions and assumptions. In many research papers and media articles, mastering engineers perform the role of ‘talking heads’ or expert witnesses and more often than not preach the negative values of hyper-compression, while at the same time defending their use of the process as the client’s wishes, and not theirs. An excellent example of this was a controversial comment made by mastering engineer Ted Jensen in regards to his mastering of Metallica’s Death Magnetic:

In this case the mixes were already brick walled before they arrived at my place. Suffice it to say I would never be pushed to overdrive things as far as they are here. Believe me I’m not proud to be associated with this one, and we can only hope that some good will come from this in some form of backlash against volume above all else (quoted in Cashmere: 2008, online).

To which Metallica’s drummer Lars Uhlrich responded:

Listen, there’s nothing up with the audio quality. It’s 2008, and that’s how we make records. Rick Rubin’s whole thing is to try and get it to sound lively, to get it to sound loud, to get it to sound exciting, to get it to jump out of the speakers. Of course, I’ve heard that there are a few people complaining. But I’ve been listening to it the last couple of days in my car, and it sounds fuckin’ smokin’ (quoted in Michaels: 2008, online).

Bob Ludwig who is an extremely well known and respected mastering engineer from the U.S. features prominently and regularly in many studies and media reports (for example see: Smith: 2008; von Ruschkowski: 2009; Acattatis: 2010; and Devine: 2013). What is surprising is that apart from gathering the opinions of a select few mastering engineers that can lend their symbolic and cultural capital to an authoritative article, which by the way also corresponds with the narrative the author intends to put forward, other areas of the production chain are often ignored. Apart from Vickers (2010) and Taylor & Martens (2014), the creative process or aesthetic concerns are rarely ever mentioned. Therefore, it is suggested that in a study of this particular topic, a wide cross section of the music industries be approached for a more comprehensive investigation.

Radio has played a crucial role in the advertising and distribution of music, and also in sustaining the use of hyper-compression; “The idea is that, especially on the radio, louder songs stand out, and attract consumers’ notice more easily” (Essling et al: 2014, p. 1). Record companies and artists have maintained “close ties to radio stations” as they form a significant part of each other’s respective business models, and it is “well-known that radio airplay is one of the central influences for music purchase decisions” (ibid). Sawyer outlines what could be described as a symbiotic relationship that exists between the two in that:

…much of popular music is created to respond to the demands and tastes of radio listeners and major advertisers. If a radio station attracts more listeners because they like the songs that the radio station is playing, advertisers will pay more money to the station to advertise to those listeners (2006, p. 230).

In the case of country music, Sawyer goes even further to suggest that radio could be considered an agent in the creative process due to the influence of advertisers; “The companies that pay for advertising time on country radio are the people who really control what gets played on country radio. In a sense, they’re the creators of country” (ibid). It is suggested therefore, that this relationship between music creation and radio station expectations has been one of the driving factors for the continued use of hyper-compression and can be viewed as a significant structural determinant of authority on the cultural production of music. Radio station music directors in particular, wield an inordinate amount of power in the music industries (Vickers: 2011) and it is common for these agents to identify production values such as loudness (or lack thereof) that do not conform to what they consider is their station sound. If a recording is desired but lacks this conformity, suggestions will then be made to the record company or artist management to provide a differently mastered version of the recording (commonly referred to as the ‘radio edit’), which acts as both an adjunct to the creative process and maintains excessive loudness in masters. Therefore, it is in the record company’s best interest to be acutely aware of these particular aesthetic or production standards. They will in turn impose restrictions (structures) on both the artists and their producers to conform to these standards; often hundreds of thousands of dollars in production and promotion costs are at stake, so adhering to the latest trends in broadcasting will be the company’s priority (Taylor: 2013, p. 60).

Largely ignored until recently in literature and directly related to hyper-compression in academic studies, is the role the audience plays as agent operating within the field. The audience forms a significant sector of the music industries and in regard to hyper-compression, many of the assumptions made regarding the audience response and preferences by many in the field are seen to drive the myth. The psychoacoustic phenomena represented as the ‘louder is better’ paradigm weigh heavily into this debate. The shift in listener habits that are a direct result of the introduction of personal media players (PMDs) have meant that “Apple’s iPod and MP3 players in general have risen to cultural prominence in recent years.” (Beer: 2008, p. 1). Beer claims that PMDs have “reconfigured and recontextualised” music away from the physical artefact to the virtual and “moved it out across the spaces of everyday life, a process that transcends boundaries between public and private zones” (ibid). Bull expands to suggest that it “gives users unprecedented power of control over their experience of time and space. They do so by managing their mood and orientation to space through the micro-management of personalised music” (Bull: 2006, p. 1). Again we can look to the hearing mechanism and psychoacoustics for answers as to how hyper-compression is related to this spatial recontextualisation that Beer mentions. PMDs have moved the listening experience away from the home to the noisy environment one experiences when in transit. This environmental noise acts as a masking agent that can interrupt the listening experience when sections of the music fall below the noise level (Bull: 2006; Hodgetts et al.: 2007; Beer: 2008; Epstein et al.: 2010; Levey et al.: 2011; Vickers: 2010, 2011; and Devine: 2013). It is thought that hyper-compression is a way to combat this annoyance by relegating all sections of the music to exactly the same level.

This shift in audience listening habits also instigated an enormous market for headphones, and in particular ‘celebrity headphones’ creating a multi-billion-dollar market (Feduka: 2011, online). This was exemplified by the ‘Beats’ headphone range of rap artist Dr Dre, reportedly sold to Apple Corporation for US$3billion dollars in 2014 (Solomon: 2014, online). This propelled Dre to the top spot of Forbes magazine “annual list of musician millionaires”; confirming him as the highest paid musician for 2014 (Michaels: 2014, online). The second spot awarded to Beyoncé was “over half a billion dollars behind the NWA co-founder” (ibid). Even more astonishing was that Dre earned more than the entire top ten combined, including Paul McCartney, Justin Bieber and One Direction (ibid).

The music industries have a large base of agency within the audience that represents a spectrum from the novice to the expert (prosumer). There is a naturally instinctive response to music that does not require the same level of acquired knowledge for basic involvement that domains such as mathematics or physics demand (Levitin: 2006, p. 57). The average listener who only listens and therefore can critique music has an equal and valid presence within the field as any other agent. Vickers (2010) lists an extensive range of speculations and assumptions concerning audience expectations of hyper-compressed music that had remained up to that point unexplored by research; studies into listener preferences and the perception of dynamic range is relatively new (for example see: Croghan and Arehart: 2012; HjortKjaer et al.: 2014; Taylor and Martens: 2014; Wendl and Lee: 2014 and Ronan et al.: 2014). Taylor & Martens question whether the audience can detect hyper-compression, actually know what it is or what their preference would be:

Surprisingly, despite this now dominant paradigm in creative music production, there exists a conspicuous lack of rigorous investigation in this area. This suggests that listener preferences remain relatively unknown. Is the average listener aware of the significantly reduced dynamic range of the popular music they generally listen to? The answer would most likely be no. However, given the chance to choose an alternative, what would they prefer? (2014, p. 1).

Related to audience response there has been speculation as to a connection between ‘loud’ masters and sales figures of music, reinforcing “the belief that increased loudness will translate into additional sales” (Vickers 2011: p. 346). Viney analysed 30 recordings from the UK charts and concluded that “there is no evidence of any significant correlation between loudness (and implied compression) and commercial success” and this “encourages further research into the ‘actual’ factors determining success” (2008, p. 54). He does however make the point that sales success is “closely interlinked with radio and TV airplay” and the loudness of the music track may initially influence the decisions made by these broadcast companies as to what tracks will be featured, but does not affect the audience’s opinion directly (ibid, p. 55). Vickers discovers a similar result for the US Billboard charts. He concludes that, “in general, content trumps loudness” (2011, p. 350), but there is the “possibility that the various music industry gatekeepers, who decide which songs get airplay and other types of promotion, may demand hyper-compression due to a firm belief that consumers prefer louder songs” (Vickers: 2011 p. 349). This supports Viney’s assumption that loudness could contribute to the success indirectly by attracting support from the industry gatekeepers of the field. Furthermore, it adds weight to the argument that artists use loudness as a method of entry into the field and what McIntyre aptly describes as the “arena of social contestation” (2008, p. 1).

Conclusion

There are of course myriad other factors to consider that contribute to this discussion overall but are beyond the scope of this paper. In a larger study, the creative system of music production would be expanded to address the ‘aesthetic’ (apart from a cultural and economic capital rationale) functioning within the ‘louder is better’ paradigm: the realm of aesthetic judgment. Loudness can also be viewed as “a production aesthetic in response to the development of digital technology” and that “the technology and ‘loudness’ itself signified a distinct transformation in the representation of some genres of music” (Taylor and Martens: 2013, p. 2). While some genres, such as classical and jazz, have remained relatively entrenched in static form by comparison to contemporary genres, there are others that have become defined by the technological advancements in music production such as EDM (electronic dance music). Loudness has become an integral part of the way EDM is constructed compositionally utilising ‘tension and release’ as an effective method of creating excitement (for example see: Skrillex: 2011). Aesthetic judgment is a subjective union of sensory, emotional and intellectual responses to art, culture and nature. Consequently, using scientifically measurable assessments of sense perception as the only criterion for forming a judgment is clearly problematic. This again serves as a reminder that a systems approach to analysis in this instance could be argued as both beneficial and constructive to the discussion. The continued use of hyper-compression by audio practitioners should suggest that there are defensible aesthetic or creative justifications for employing hyper-compression. These justifications should also be in line with listener expectations.

There is a great deal of both empirical and anecdotal evidence that supports the premise that the ‘louder is better’ paradigm is responsible for this quest for loudness, which was evident throughout the vinyl era and continued on into the digital technology era with even greater emphasis. Due to the non-linearity of frequency response of the human hearing mechanism, when music is louder we tend to perceive low and high frequencies with greater detail and therefore achieve a more desirable listening experience. It is widely reported in the literature that this premise is the central determinant behind the use of hyper-compression by those involved in the music industries, even at the suggested expense of audio quality. Furthermore, hyper-compression and its use is most likely not solely attributable to this one phenomena of the hearing mechanism and there may be other factors in play that require investigation.

It is argued that the diffusion of digital technologies and their increasing affordability facilitated the proliferation of hyper-compression. This, coupled with an increasingly competitive marketplace, new dominant forms of playback and reproduction, and the aforementioned ‘louder is better’ paradigm (and the many assumptions surrounding this), it is also argued that hyper-compression has moved away from being an agent’s choice to that of a structural determinant in the production of popular music. This movement from agent to structure is evidence of: the dynamic inter-relationships of agency and structure; the systematic nature of creative production; and, that ‘techno-capital’ is a key element in the music industries. However, this form of technology-based capital is not a technological determinist argument as all of the other forms of Bourdieu’s concept of capital are still at play within the system of music production, promotion and consumption as explained.

Current research surrounding the use of hyper-compression can arguably be viewed as disproportionately scrutinised from a scientific perspective with inadequate consideration for either aesthetic concerns or the economic and sociocultural pressures audio practitioners may experience from their clients. Clients, who themselves consider hyper-compression as a structure imposed on them by the field of cultural production as a condition of entry into the highly competitive marketplace that is the world of music dissemination. Despite the evidence that science presents with regards to the hyper-compression process being deleterious to audio quality, its use has continued regardless with little to suggest otherwise. The subject of hyper-compression and its use has been at the centre of extensive debate during the past decade, illuminating a distinct tension between the empirical evidence of applied science and the subjective interpretation of creative agents. It has therefore been the aim of this paper to present a framework for an investigation of these tensions that embraces a systems approach rather than addressing either individually. In addition, it is hoped that this framework will help to provide a platform for the future development of a new interpretive model to adequately explain both the objective audio qualities of mastered audio and how this is subjectively received by those engaged in the creation of music, the critique of music or those that listen to music.

References

Accattatis, M. (2010) The Loudness Race: A Post Human Interpretation. Essay. [On-line] August 6. http://www.accattatis.com/words/loudnessrace.pdf (Accessed: 19 October 2013)

Anderson, T. (2008) ‘Will the Loudness Wars Result in Quieter CDs?’ In: The Guardian. [On-line] January 10. Guardian News and Media Limited, London, UK. Available at: http://www.guardian.co.uk/technology/2008/jan/10/digitalmusic (Accessed: 27 July 2014)

Beer, D. (2008) ‘The Iconic Interface and the Veneer of Simplicity: MP3 Players and the Reconfiguration of Music Collecting and Reproduction Practices in the Digital Age.’ In: Journal of Information, Communication & Society. 11, 1, June, pp. 71-88.

Bourdieu, P. (1990) The Logic of Practice. Cambridge: Polity Press, UK.

Bourdieu, P. (1993) The Field of Cultural Production. Columbia University Press and Polity Press in association with Blackwell Publishers, US, UK.

Bourdieu, P. (1996) The Rules of Art Genesis and Structure of the Literary Field. Cambridge: Polity Press, UK.

Bull, M. (2006) ‘No Dead Air! The iPod and the Culture of Mobile Listening.’ In: Journal of Leisure Studies. 24, 4, August, pp. 343-358.

Cashmere, P. (2008) Metallica Recording Engineer Ted Jensen Craps on Death Magnetic. In: Undercover. [On-line] September 28. Undercover Network Pty Ltd, Melbourne, Australia. Available at: http://www.undercover.fm/news/6357-metallica-recording-engineer-ted-jensen-craps-on-death-magnetic (Accessed: 2 Nov 2014)

Clark, C. (2009) The Loudness Wars: Why Music Sounds Worse. In: NPR Music. [On-line] December 31. National Public Radio Inc., Washington D. C., USA. Available at: http://www.npr.org/2009/12/31/122114058/the-loudness-wars-why-music-sounds-worse (Accessed: 27 July 2014)

Croghan, N. B., Arehart, K. H. and Kates, J. M. (2012) ‘Quality and Loudness Judgments for Music Subjected to Compression Limiting.’ Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 132, 2, August., pp. 1177-1188.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1988) Society, culture and person: A Systems View of Creativity in The nature of creativity: Contemporary psychological perspectives. Sternberg, R. (ed.). Cambridge: University Press, New York, pp. 325-9.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1997) Creativity: Flow and the Psychology of Discovery and Invention. New York: Harper Collins.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1999) Implications of a Systems Perspective for the Study of Creativity in Handbook of creativity, R. Sternberg (ed.). New York: Cambridge University Press, USA, pp. 313-335.

Deruty, E. (2011) ‘Dynamic Range’ and the Loudness War’. In: Sound On Sound. [On-line] September edition. SOS Publications Group, Cambridge, UK. Available at: http://www.soundonsound.com/sos/sep11/articles/loudness.htm (Accessed: 3 March 2013)

Deruty, E., Tardieu. (2013) ‘About Dynamic Processing in Mainstream Music, 1967-2011.’ In: Journal of the Audio Engineering Society. 54, 3, February, pp. 1-11.

Devine, K. (2013) ‘Imperfect Sound Forever: Loudness Wars, Listening Formations and the History of Sound Reproduction.’ In: Journal of Popular Music. 32, 2, pp. 159-176.

Donahue, M. (2010) ‘The Loudness War.’ In: Performer Magazine. [On-line] July 5. Performer Publications Inc., Somerville, MA, USA. Available at: http://performermag.com/Archives/loudness.php (Accessed: 3 March 2013)

Emery, C. (2007) ‘Audio Gain in Volume Signals Loss for Listeners.’ The Baltimore Sun. [On-line] November 25. Maryland, USA. Available at: http://articles.baltimoresun.com/2007-11-25/news/0711250027_1_hearing-loss-sound-engineer-seldon-plan (Accessed: 14 July 2014)

Epstein, M., Marozeau, J. and Cleveland, S. (2010) ‘Listening Habits of iPod Users’. In: Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 53, pp. 1472–1477.

Essling, C., Peukert, C., and Koenen, J. (2014) ‘Another Loudness War: How Record Labels Compete for Consumer Attention’. In: Working Paper. [On-line] May 31. The University of Zurich. Available at: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2444708 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2444708 (Accessed: March 2014)

Fekadu, M. (2011) ‘Celebrity Headphones the Next Status Symbol.’ In: The San Francisco Chronicle. [On-line] December 27. Associated Press, CA, USA. Available in: http://www.sfgate.com/business/article/Celebrity-headphones-the-next-status-symbol-2426166.php#ixzz26kcX8jhR (Accessed: 3 March 2014)

Fletcher, H. and Munson, W. A. (1933) ‘Loudness, Its Definition, Measurement and Calculation.’ In: Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 5, October, pp. 82-108.

Giddens, A. (1984) The Constitution of Society. Los Angeles: University of California Press.

Hodgetts W.E., Rieger J.M. & Szarko R.A. (2007) ‘The Effects of Listening Environment and Earphone Style on Preferred Listening Levels of Normal Hearing Adults Using an MP3 player.’ In: Ear Hear. 28, pp. 290–297.

Haralambos, M. and Holbern M. (1995) Uniting Structural and Social Action Approaches. In Sociology: Themes and Perspectives. Fourth edition. London: Collins, pp. 903-907.

Hjortkjær, J & Walther-Hansen, M. (2014) ‘Perceptual Effects of Dynamic Range Compression in Popular Music Recordings’. In: Journal of the Audio Engineering Society. 62, 1/2, January/February, pp. 37-41.

Inglis, S. (2011) ‘Is Loud Music Better?’ In: Sound On Sound. [On-line] March edition. SOS Publications Group, Cambridge, UK. Available at: http://www.soundonsound.com/sos/mar11/articles/loudness.htm (Accessed: 23 Feb 2014)

ISO (International Organisation for Standardisation). (2013) ISO 226:2013, Normal Equal-loudness Contours. Second edition.

Jones, S. (2005) ‘The Big Squeeze: Mastering Engineers Debate Music’s Loudness Wars. In: Mix Magazine. [On-line] December 1. New Bay Media, New York, NY, USA. Available at: http://mixonline.com/mag/audio_big_squeeze (Accessed: 23 February 2014)

Katz, B. (2010) ‘Compression’. In: Online blog. [On-line] Available at: http://www.digido.com/compression.html (Accessed: may 2015)

Lamere, P. (2009) ‘The Loudness War Analysed’ In: Personal Blog – Music Machinery. [On-line] March 3. Available at: http://musicmachinery.com/2009/03/23/the-loudness-war (Accessed: 23 February 2014)

Levey, S., Levey, T. and Fligor, B. J. ‘Noise Exposure Estimates of Urban MP3 Player Users.’ In: Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 54, pp. 263–277.

Leviton, D. (2006) This is Your Brain on Music: Understanding a Human Obsession. London: Atlantic Books, UK.

Lund, T. (2004) ‘Distortion to the People’. In: Resolution, The Audio Production Magazine. [On-line] March. http://www.resolutionmag.com/pdfs/TECHNO~1/DISTOR~1.PDF (Accessed: 19 January 2013)

Lund, T. (2006) ‘Stop Counting Samples.’ In: Proc. of the 121st Convention of the Audio Engineering Society. San Francisco, CA, USA.

Lund, T. (2007) ‘Audio Delivery Specification’ In: Proc. of the 123rd Convention of the Audio Engineering Society, New York, USA.

Martin, G. and Pearson, P. (2005) With a Little Help From My Friends: The Making of SGT Pepper. London: Little Brown & Co, UK.

Masterton, K. (2008) ‘Loudness War Stirs Quiet Revolution by Audio Engineers.’ In: Chicago Tribune. [On-line] January 4. Chicago, IL, USA. Available in: http://articles.chicagotribune.com/2008-01-01/news/0801010011_1_loud-compressed-recording (Accessed: 14 July 2014)

Mauch, M. (2011) ‘Anatomy of the UK Charts. Part 4: Survival of the Flattest.’ In: Last HQ Blog. [On-line] July 5. lastfm.com, London, UK. Available at: http://blog.last.fm/2011/07/15/anatomy-of-the-uk-charts-part-4-survival-of-the-flattest (Accessed: 9 August 2015)

McIntyre, p. (2012) ‘How are Messages Created?: Changes in Thinking about Communication Theory Leading to a New Synthesis.’ In: Proc of the ANZCA Conference. Adelaide, South Australia.

Metallica (2008) Death Magnetic [CD]. Warner Bros, Vertigo.

Michaels, S. (2012) ‘Pop Music These Days: it all Sounds the Same, Survey Reveals. In: The Guardian. [On-line] July 27. Guardian News and Media Limited, London, UK. Available at: http://www.guardian.co.uk/music/2012/jul/27/pop-music-sounds-same-survey-reveals (Accessed: 2 November 2014)

Michaels, S. (2014) ‘Dr Dre Tops Forbes’ Highest Paid Musician List.’ In: The Guardian. [On-line] December 27. Australian Edition. Guardian News and Media Limited, London, UK. Available at: http://www.theguardian.com/music/2014/dec/11/dr-dre-tops-forbes-highest-paid-musician-list-beats (Accessed: 23 February 2013)

Michaels, S. (2008) ‘Death Magnetic ‘Loudness War’ Rages On.’ In: The Guardian. [On-line] October 1. Australian Edition. Guardian News and Media Limited, London, UK. Available at: http://www.theguardian.com/music/2008/oct/01/metallica.popandrock (Accessed: 23 February 2013)

Milner, G. (2010) Perfecting Sound Forever: An Aural History of Recorded Music. New York: Faber and Faber, USA.

Moore, B. C. J. (1989) An Introduction to the Psychology of Hearing. Third edition. London: Academic Press Limited, UK.

Nielsen, S. H. and Lund, T. (1999) ‘Level Control in Digital Mastering.’ In: Proc. of the 107th Convention of the Audio Engineering Society. New York, NY, USA.

Nielsen, S. H. and Lund, T. ‘Overload in Signal Conversion.’ Proc. of the 23rd International Conference of the Audio Engineering Society, Copenhagen, Denmark, May.

Nielson, S. H. and Lund, T. (2000) ‘dBFS + Levels in Digital Mastering.’ In: Proc. of the 109th Convention of the Audio Engineering Society, Los Angeles, California, USA.

Oasis (1994) What’s the Story Morning Glory? [CD]. Creation Records.

O’Casey, M. (2011) ‘Queen: Days of Our Lives.’ Documentary. Globe Productions, BBC Worldwide. London, UK. Published: June 27. (Accessed: 23 February 2013)

Reierson, G. (2011) ‘The Loudness War is Over.’ In: Mix Magazine. [On-line] February 8. New Bay Media, New York, NY, USA. Available at: http://mixonline.com/mixline/reierson_loudness_war_0802 (Accessed: 23 February 2013)

Ronan, M., Sazdov, R., Ward, N. (2014) ‘Factors Influencing Listener Preference for Dynamic Range.’ In: Proc. of the 137th Convention of the Audio Engineering Society, Los Angeles, USA.

Rumsey, F. (2010) ‘Mastering in an Ever Expanding Universe.’ In: Journal of Audio Engineering Society. 58, 1/2, January/February, pp. 65-71.

Roger, E. M. and Kincaid, D. L. (1981) Communication Networks: Toward a New Paradigm for Research. London: The Free Press, Macmillan Publishing, UK.

Rothenberg, A. and Hausmann, C. (eds.) (1976). The Creativity Question: A Reader. Durham: Duke University Press, NC, USA.

Sawyer, R.K. (2006) Explaining Creativity: The Science of Human Innovation. New York: Oxford University Press, USA.

Schirato, T. and Yell, S. (2000) Communication and Cultural Literacy. Second edition. Sydney: Allen and Unwin, Australia.

Skrillex (2011) Bangarang [CD]. Atlantic, Big Beat and OWSLA.

Smith, E. (2007) ‘Sales of Music, Long in Decline, Plunge Sharply.’ In: The Wall Street Journal. [On-line] March 21. New York, NY, USA. Available at: http://online.wsj.com/article_email/SB117444575607043728-lMyQjAxMDE3NzI0MTQyNDE1Wj.html (Accessed: 23 February 2013)

Smith, E. (2008) ‘Even Heavy-Metal Fans Complain that Today’s Music is Too Loud!!!’ In: The Wall Street Journal. [on-line] September 25. New York, USA. Available at: http://online.wsj.com/article/SB122228767729272339.html (Accessed: 23 February 2013)

Soloman, B. (2014) ‘It’s Official: Apple Adds Dr. Dre With $3 Billion Beats Deal.’ In: Forbes. [On-line] May 28. Forbes Media, Jersey City, NJ, USA. Available at: http://www.forbes.com/sites/briansolomon/2014/05/28/apple-brings-dr-dre-on-board-with-official-3-billion-beats-deal (Accessed: 6 March 2014)

SOS (2010), ‘25 Productions that Made History.’ In: Sound On Sound. [On-line] November. Cambridge, United Kingdom. Available at: http://www.soundonsound.com/techniques/25-productions-made-history (Accessed: 13 February 2013)

Southall, H. (2006) ‘Imperfect Sound Forever.’ In: Stylus Magazine. [On-line] May 1. Brooklyn, NY, USA. Available at: http://www.stylusmagazine.com/articles/weekly_article/imperfect-sound-forever.htm (Accessed: 13 February 2013)

Sreedhar, S. (2007) ‘The Future of Music: Tearing Down the Wall of Noise.’ In: IEEE Spectrum. [On-line] August edition. IEEE, New York, NY, USA. Available at: http://spectrum.ieee.org/computing/software/the-future-of-music (Accessed: 23 February 2013)

Sternberg, Robert (ed). (1999) Handbook of Creativity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, UK.

Taylor, R. W. (2013) Turn It Up, Play It Loud – Hyper-compression in Music Production: Listener Preferences on Dynamic Range Reduction. Master of Design Science Dissertation. The University of Sydney.

Taylor, R. W. and Martens, W. L. (2014) ‘Hyper-compression in Music Production: Listener Preferences on Dynamic Range’. In: Proc. of the 136th Convention of the Audio Engineering Society. Berlin, Germany.

Thiele, N. (2005) ‘Some Thoughts on the Dynamics of Reproduced Sound.’ In: Journal of the Audio Engineering Society. 53, 1/2, January/February, pp. 130-132.

van Krieken. R., Smith, P., Habibis, D., Hutchins, B., Haralambos, M. and Holborn, M. (2005) Sociology: Themes and Perspectives. Third Australian edition. Sydney: Pearson Education, Australia.

Vickers, E. (2010) ‘The Loudness War- Background, Speculation and Recommendations.’ In: Proc. of the 129th Convention of the Audio Engineering Society. San Francisco, CA, USA.

Vickers, E. (2011) ‘The Loudness War: Do Louder, Hyper-compressed Recordings Sell Better?’ In: Journal of Audio Engineering Society. 59, 5, May, pp. 346-351.

Viney, D. (2008) The Obsession with Compression. Master of Music Technology Thesis. London College of Music, Thames Valley University.

von Ruschkowski, A. (2009) ‘Loudness War.’ In: Proc. of the VDT – Seminar “An Eye On Hearing“. Munich, Germany.

Weymouth, D. (2012) The Loudness War: A Game and Market Theory Analysis. Essay. Munich: GRIN publishing, Germany. November 30.

Wendl, M. and Hyunkook, L. (2014) ‘The Effect of Dynamic Range Compression on Loudness and Quality Perception in Relation to Crest Factor.’ In: Proc. of the 136th Convention of the Audio Engineering Society. Berlin, Germany.

Williamson, J. and Cloonan, M. (2007) ‘Rethinking the Music Industry”. In: Journal of Popular Music. 26, 2.

Wilson, N., Stokes, D. and Blackburn, R. (2001) Banking on a Hit. London: DCMS, UK.

Notes:

[1] Dynamic range compression (DRC), or simply ‘compression’ is a common audio production process used to re-map the dynamic range of an audio signal. Hyper-compression is an extreme variant of DRC that drastically reduces dynamic range. Hyper is a prefix with Greek origins meaning ‘over’ and used in the formation of many compound words such as hyperthyroid or hyperactive. A more detailed explanation of hyper-compression can be found in Vickers, 2010.

[2] ‘Perceived loudness’ is a fundamental element in regards to the perception of sound within the discipline of psychoacoustics. “Loudness is defined as that attribute of auditory sensation in terms of which sounds can be ordered on a scale extending from quiet to loud” and “that loudness is a subjective quantity and cannot be measured directly” (Moore, 1989, p. 47). The term ‘loudness’ as commonly used in much of the literature, is scientifically imprecise in its direct meaning, however, it has become part of the common vernacular to describe how ‘loud’ a signal will be perceived by the listener when reproduced. An algorithm has been developed to predict correlation between signal and perceived loudness (ITU BS 1770-3), currently being implemented as a standard in broadcast production via the EBU R-128 recommendations. Refer to references for more information.

[3] The term ‘hot’ is a descriptive term to represent a very large magnitude of signal recorded onto a given media, in particular, analogue media. Achieving a ‘louder cut’ on vinyl was considered highly desirable by artists and the American mastering and pressing plants were by far the most successful.

[4] Apart from dynamic range compression (DRC), a number of other methods were utilised in order to achieve a high level of perceived loudness, in particular, equalisation: “In order to combat the poor high frequency response of AM radios and portable record players, and to mask the second harmonic distortion of the midrange (due to “tracing” distortion during mastering), levels were boosted in the 8-10 kHz region. Low bass frequencies were filtered out using a 70 Hz brick wall high-pass filter, and perception of the low bass was restored by boosting the second harmonic of the bass guitar.” (Vickers, 2010, p. 3.)

[5] Achieving loudness on vinyl records is problematic in that there are trade-offs between total playing time and the amount of overall level and the amount of bass that can be recorded onto the vinyl. Cutting a song with higher level means the grooves become wider and thus less playing time, and similarly, cutting a song with heavy bass means the grooves must be deeper with the same outcome. There can also be issues with being able to play ‘hot’ cuts with some record players as the needle can jump out of the groove if the bass and level are too high. Many cutting engineers consider getting the balance between level and playability of the record as an art-form that requires considerable knowledge and experience.

[6] “BBC News Story about Oasis and the Mastering Engineer behind the BRITs “best album of the past 30 years”. Uploaded to YouTube on Feb 22, 2010. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=n8Wtfv5GExk

[7] Interview with Owen Morris, the producer of What’s the Story Morning Glory by Oasis. http://www.oasis-recordinginfo.co.uk/?page_id=250